To say that Raymond Chandler described Los Angeles as ‘a city with the personality of a paper cup’ isn’t quite right. Even when the phrase is quoted correctly, the sentence almost always has its curdled opening omitted. What he actually has Philip Marlowe say, in The Little Sister, is:

The luxury trades, the pansy decorators, the Lesbian dress designers, the riff-raff of a big hard-boiled city with no more personality than a paper cup.

The mean-mindedness of the beginning of the sentence undercuts the laconic zinger at its end, and makes one question whether either Los Angeles or a paper cup truly wants for personality. Hollywood has mixed feelings about its home turf: seedy and corrupt in LA Confidential, a place of strange magic in LA Story. Out-of-towners are divided about the place too, but for every Woody Allen (‘a city where the only cultural advantage is being able to make a right turn on a red light’) there’s someone like the writer and critic Reyner Banham whose short film Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles is as giddy an encomium as its title suggests. Whatever the place’s pros and cons, personality doesn’t seem to be its problem.

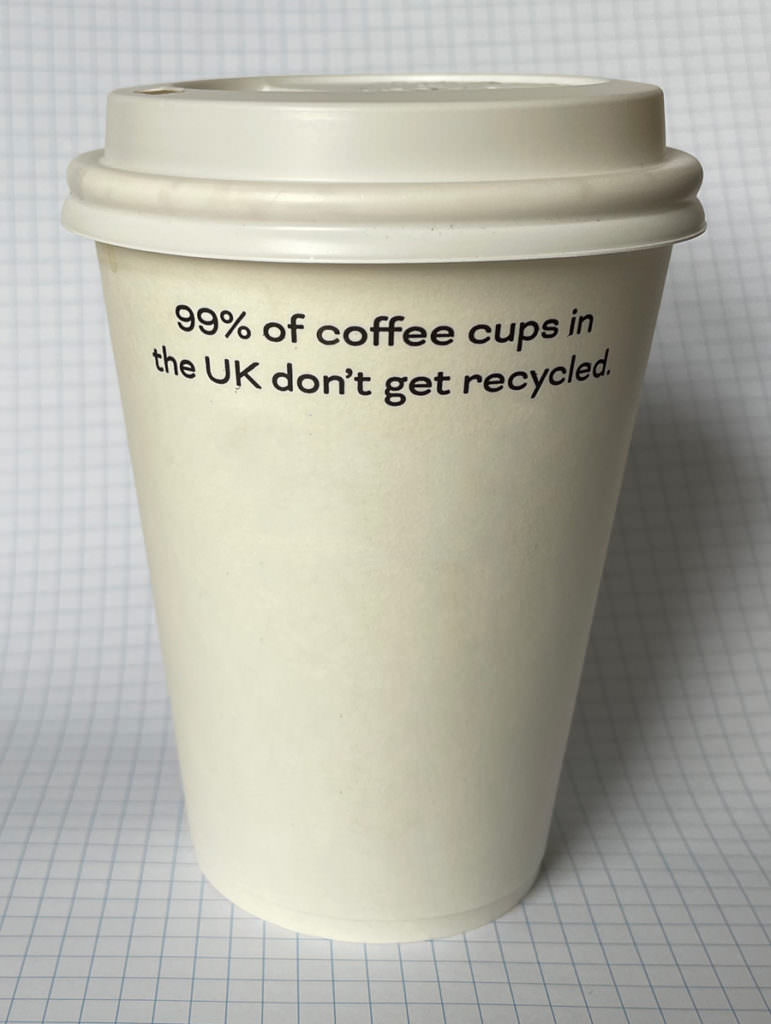

Paper cups, and their plastic successors, are difficult to defend ethically. Their current status is as environmental despoilers of the first rank – the epitome of the disposable culture and sinful single use.

But culturally, these humble objects deserve a bit of respect, and if the love of the things is aesthetic, it’s possible, guiltlessly, to have one’s cup and drink from it too. I have a couple of trompe l’oeil ceramic versions which mimic disposable ones. The first shown here is modelled on the infuriatingly flimsy plastic type which, when filled with a hot drink, scald the hand and crumple under the slightest pressure.

It is from ones very like this that Peter Falk, playing the fallen angel ‘Peter Falk’ in Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire, happens to be drinking when he speaks to the invisible angels who are benevolently haunting still-divided Berlin. In one of these scenes Falk detects the presence of the angel Damiel (Bruno Ganz) and says to him:

I can’t see you but I know you’re here. I feel it. You’ve been hanging around since I got here. I wish I could see your face. Just look into your eyes and tell you how good it is to be here, just to touch something. See that’s cold . . . I feel good. Here . . . to smoke . . . have coffee. And if you do it together it’s fantastic.

The scene wouldn’t work if he was drinking from Meissen china and smoking a Montecristo in a grand salon. That would be about the pleasures of luxury and privilege, about being halfway to heaven. Cheap coffee from a plastic cup in wintery weather at a shabby currywurst stand is about the transcendent ordinariness of being human.

Steven Spielberg is a filmmaker who can get a lot from a lot and a lot from a little. He used the same kind of cup, getting it to do comedy, in Jaws. The drawn-out pissing contest between Hooper (Richard Dreyfus) and Quint (Robert Shaw) is played out in several scenes, but the best is the beer can v. plastic cup face off. In Jurassic Park, when pricy animatronics had been superseded by even more expensive CGI, anything that suggested rather than showed saved thousands of dollars per second of screen time. Spielberg got the movie’s most effective moment of suspense from nothing more than a couple of trembling water beakers on an SUV’s dashboard.

The other half of my collection is a souvenir of New York, a copy of the Anthora coffee cup. Designed by Leslie Buck, a marketing executive for the Sherri Cup Company, the Anthora has been around since 1963, and even if it isn’t technically exclusive to New York, after Milton Glaser’s I♥︎NY it is arguably the most recognisable graphic shortcut to the city.

The association of America’s Greek community with selling coffee is a long-standing one which Buck recognised and saw the potential for having graphic fun with. The Anthora’s design, a slightly goofy evocation of Helenic antiquity, largely in the colours of the Greek flag, offered diners and coffee shops something displaying a friendly message with a dash of hyphenate-American pride. And as a curious, free-floating non-brand (the cup itself is a brand I suppose, but what goes in it isn’t Anthora coffee, or We Are Happy to Serve You coffee, it’s whatever coffee the place happens to serve) it became phenomenally visible, both in the city, and, later, in movies and TV shows. I remember thinking when watching Mad Men, on one of the occasions when the action shifted from New York to California, that the series must have had quite a budget to do so much West Coast location shooting. But of course I was being thick. The staff of Sterling Cooper and their New York homes and offices were already there, on the sound stages of Los Angeles Center Studios. It was the cup that flew in from the other coast. For productions not shot in New York the cup does this sort of work often. It’s a cheap and effective prop to place action in the city, and more subtle than an establishing shot (often on glaringly mismatched film stock) of the Lower Manhattan skyline.

If the Anthora ever was aspirational (most products featured in Mad Men were one way or another) it isn’t any longer. Any cachet it had has declined with the rise of Starbucks and other chains. In movies it’s no longer in the hands of the princes of ad-land, but in those of shlubbier folk like Robert De Niro’s bail bond bounty hunter in Midnight Run or John Turturro’s skid row defence attorney in The Night Of. When characters are seen with the blue and white beaker, we know they are deaf to the siren call of incomers like the green mermaid from Seattle.

¶ Images. Any images included in this post may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license. ¶ Notes. A slightly scrappy video-to-digital transfer of Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles can be seen on YouTube.